Making Our Own Refuge

It is common for people to go through phases of practice where commitment, confidence, or trust feels weak. Even people who have been on the path for a long time can have such phases. However, the difference between a beginner and an experienced practitioner lies in how they meet such periods. People with more practice tend to have a better sense of their own sources of refuge, and hence are better able to correct for, or simply weather, these losses of confidence.

It is worthwhile to reflect on, and even experiment with, what for you enhances the quality called saddhā, usually translated as faith, trust, or confidence. What is inspiring? What reminds you of your interest in developing your mind and practicing the Dharma? What assures you that even a significant challenge can be met with Dharma practice?

In this piece, I offer a wide range of what could be called objects of faith. They tend to fall into a handful of categories: Other people, the five senses, the cognitive mind or the heart-mind (citta), and actions. Which have been meaningful for you? Are there areas that you generally don’t consider and might want to try?

Other People

The Dharma is visible in the faces, comportment, and presence of people who are well-practiced. Something shines in the eyes of dedicated monastics, teachers, and longtime practitioners, and their very movements reflect composure and attentiveness.

One time I was in the middle of a several month retreat, and Joseph Goldstein, who is a wonderful elder in this tradition, arrived to teach. He came while we were sitting, and I opened my eyes slightly and saw him walking across the front of the room. I felt my body sit up a bit straighter and some uplift came into my heart. It wasn’t about Joseph personally – I recognized it immediately as the experience of saddhā. It was evoked simply by the way he was carrying himself.

Interacting with such people adds a further dimension. They model careful listening, compassion, and wisdom, such that our heart can be touched even by a simple conversation. Good spiritual friends (kalyāna mitta) also serve as prompts to recall our faith.

The Five Senses

The five physical senses – seeing, hearing, smelling, tasting, and touching – are often associated in Buddhist teachings with the need for restraint. But not all sense stimuli are to be avoided or restrained. Some evoke faith, when we are properly attuned.

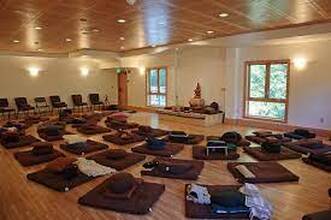

For some, seeing objects such as Buddha statues or images, stupas or relics, or even monastic robes, evokes faith. The beauty of a retreat center or simple aesthetic of a monastery can uplift the mind, as can the more subtle sense of calm and silence in a meditation hall.

Hearing the Dharma has long served as a gateway to profound insight, and even at a more ordinary level can greatly inspire the heart. With the vast number of talks and guided meditations available today, listening can be a ready resource to support practice.

Being in nature also offers a glimpse of the Dharma that might sometimes penetrate more deeply than explicitly spiritual images or words. Trees, bees, clouds, and streams demonstrate impermanence, impersonality, and conditionality in a straightforward way. The truth of nature can heal and clarify.

The Cognitive Mind and the Citta

Interestingly, the thinking mind is not left out of faith. The Buddha encourages reflection on the teachings, both in the abstract and in the way that they correspond to our experience. For many early-stage practitioners, the first taste of real confidence comes when the person realizes that meditation has changed some habit or reduced immediate suffering. The mind can indeed be trained. The process works.

We may also be inspired by hearing stories of other people gaining faith or overcoming suffering, such as in the suttas or more contemporary examples. Kisagotami, distraught with grief, carried her dead child to the Buddha. He asked her to retrieve a mustard seed from a household that had not experienced any deaths. Of course, she could not, and we may resonate with her grief, her wise insight, and the Buddha’s compassion all at once.

Many people find a sense of trust in the wisdom texts of the Pāli Canon. Knowing that they were composed many centuries ago across the world somehow lends credence to their profundity because they point to aspects of the mind that we can observe here and now. Anger being like a “careening chariot” (Dhp 222) might suddenly make sense. And then we can allow some faith in deeper possibilities that we may not have experienced yet, such as samādhi or anattā.

Now we are moving into the realm of the citta, the heart-mind or spiritual sensibility. The citta can be directly touched by some experiences, evoking faith. Perhaps surprisingly, dukkha (suffering or stress) can lead to faith (SN 12.23). This is a skillful response in which we intuit a path out of suffering by avoiding our habitual response of craving relief and identifying with problems. The Buddha responded with faith when, touched by the dukkha of the human condition, he set out on his quest for liberation rather than continue a path of avoidance through the enjoyment of pleasure. Many practitioners can recall a moment of making a similar choice in the face of pain or distress.

The experience of faith is one of intuiting a space of possibility just beyond the edge of what we know. It includes a brightening of the mind and a pleasant feeling that has nothing to do with sensuality, so that it can coexist even with pain or sorrow. There is an energetic movement to faith, drawing upward or slightly forward – a movement toward, even if we don’t know toward what. Perhaps the way a plant is drawn toward the sun.

Learning to recognize the experience helps strengthen it, and at times, we might even evoke it deliberately. The upper-body posture of Buddha images, with the chest slightly forward, conveys confidence. Sitting in this way helps us touch into our own saddhā, even if it feels weak.

Actions

Faith is meant to have a motivational aspect also. As the first of the Five Spiritual Faculties, faith includes the willingness to put effort (the second faculty) toward something we value. When we have faith, we will put out energy; conversely, we are unlikely to make effort toward things in which we have no faith.

Thus, many actions arise from, or are expressions of faith. But it is also true that these same actions can evoke faith. Perhaps the quintessential act of Buddhist devotion is taking refuge in Buddha, Dhamma, and Sangha. This is done formally on retreats and sometimes in ceremonies offered at Dharma centers, but it can also be done simply before each sit or at times when the mind feels shaky.

When I participated in a simple but formal refuge ceremony at my first Dharma center, I was surprised that it brought forth powerful waves of joy (pītī) in my body. Something deep inside knew that this was important and right for me. Not being very interested in ceremony at the time, I discovered this new dimension of myself through the action.

Longer-term actions that support confidence include going on retreat or doing certain kinds of compassionate service. In reaching out beyond our own needs and typical daily patterns, we can strengthen the heart’s capacity to meet challenges in wholesome, wise, and flexible ways.

There are also many other devotional actions. Reciting or chanting the Dharma, ritual, bowing, and prayer are all options that are available, even within the early Buddhist and Theravāda traditions, which generally have fewer such things than other forms of Buddhism. Done well, these acts reduce self-focus because they are not really about you. They are done as offerings, from whatever state of mind one is in at the time. We do the chant the same way whether we happen to be angry, tired, or joyful that day. Faith increases as we are less entangled in self and can simply connect with the heart qualities evoked by the devotion.

I have enjoyed working with my altar over the years. It always houses a few meaningful items, but they rotate in and out depending on what feels important in my practice. When I go to a self-retreat center, I spend some time the first day gathering items from nature to create a simple altar. I sit with it every day, and then have a ritual of re-scattering the items back to nature when the retreat is over.

Internal Refuge

As you can see, there are many ways to support saddhā. Not all of these are appropriate for everyone, or for all times. But if you have several in your toolbox, you can see what works in a given situation of waning saddhā.

Perhaps the hardest part is remembering to check this list, which is why it is best to experientially explore it, so it gets into your bones, so to speak. In that way, these actions and mindstates become available to serve the path when needed. They become refuges.

Eventually, the heart can supply its own refuge, either by spontaneously doing one of the above, or through accessing its own deep confidence, wisdom, love, or compassion. Simply touching into our own heart can summon saddhā once we have practiced thoroughly with some of the items above.

Perhaps it is interesting to try a new one?

It is common for people to go through phases of practice where commitment, confidence, or trust feels weak. Even people who have been on the path for a long time can have such phases. However, the difference between a beginner and an experienced practitioner lies in how they meet such periods. People with more practice tend to have a better sense of their own sources of refuge, and hence are better able to correct for, or simply weather, these losses of confidence.

It is worthwhile to reflect on, and even experiment with, what for you enhances the quality called saddhā, usually translated as faith, trust, or confidence. What is inspiring? What reminds you of your interest in developing your mind and practicing the Dharma? What assures you that even a significant challenge can be met with Dharma practice?

In this piece, I offer a wide range of what could be called objects of faith. They tend to fall into a handful of categories: Other people, the five senses, the cognitive mind or the heart-mind (citta), and actions. Which have been meaningful for you? Are there areas that you generally don’t consider and might want to try?

Other People

The Dharma is visible in the faces, comportment, and presence of people who are well-practiced. Something shines in the eyes of dedicated monastics, teachers, and longtime practitioners, and their very movements reflect composure and attentiveness.

One time I was in the middle of a several month retreat, and Joseph Goldstein, who is a wonderful elder in this tradition, arrived to teach. He came while we were sitting, and I opened my eyes slightly and saw him walking across the front of the room. I felt my body sit up a bit straighter and some uplift came into my heart. It wasn’t about Joseph personally – I recognized it immediately as the experience of saddhā. It was evoked simply by the way he was carrying himself.

Interacting with such people adds a further dimension. They model careful listening, compassion, and wisdom, such that our heart can be touched even by a simple conversation. Good spiritual friends (kalyāna mitta) also serve as prompts to recall our faith.

The Five Senses

The five physical senses – seeing, hearing, smelling, tasting, and touching – are often associated in Buddhist teachings with the need for restraint. But not all sense stimuli are to be avoided or restrained. Some evoke faith, when we are properly attuned.

For some, seeing objects such as Buddha statues or images, stupas or relics, or even monastic robes, evokes faith. The beauty of a retreat center or simple aesthetic of a monastery can uplift the mind, as can the more subtle sense of calm and silence in a meditation hall.

Hearing the Dharma has long served as a gateway to profound insight, and even at a more ordinary level can greatly inspire the heart. With the vast number of talks and guided meditations available today, listening can be a ready resource to support practice.

Being in nature also offers a glimpse of the Dharma that might sometimes penetrate more deeply than explicitly spiritual images or words. Trees, bees, clouds, and streams demonstrate impermanence, impersonality, and conditionality in a straightforward way. The truth of nature can heal and clarify.

The Cognitive Mind and the Citta

Interestingly, the thinking mind is not left out of faith. The Buddha encourages reflection on the teachings, both in the abstract and in the way that they correspond to our experience. For many early-stage practitioners, the first taste of real confidence comes when the person realizes that meditation has changed some habit or reduced immediate suffering. The mind can indeed be trained. The process works.

We may also be inspired by hearing stories of other people gaining faith or overcoming suffering, such as in the suttas or more contemporary examples. Kisagotami, distraught with grief, carried her dead child to the Buddha. He asked her to retrieve a mustard seed from a household that had not experienced any deaths. Of course, she could not, and we may resonate with her grief, her wise insight, and the Buddha’s compassion all at once.

Many people find a sense of trust in the wisdom texts of the Pāli Canon. Knowing that they were composed many centuries ago across the world somehow lends credence to their profundity because they point to aspects of the mind that we can observe here and now. Anger being like a “careening chariot” (Dhp 222) might suddenly make sense. And then we can allow some faith in deeper possibilities that we may not have experienced yet, such as samādhi or anattā.

Now we are moving into the realm of the citta, the heart-mind or spiritual sensibility. The citta can be directly touched by some experiences, evoking faith. Perhaps surprisingly, dukkha (suffering or stress) can lead to faith (SN 12.23). This is a skillful response in which we intuit a path out of suffering by avoiding our habitual response of craving relief and identifying with problems. The Buddha responded with faith when, touched by the dukkha of the human condition, he set out on his quest for liberation rather than continue a path of avoidance through the enjoyment of pleasure. Many practitioners can recall a moment of making a similar choice in the face of pain or distress.

The experience of faith is one of intuiting a space of possibility just beyond the edge of what we know. It includes a brightening of the mind and a pleasant feeling that has nothing to do with sensuality, so that it can coexist even with pain or sorrow. There is an energetic movement to faith, drawing upward or slightly forward – a movement toward, even if we don’t know toward what. Perhaps the way a plant is drawn toward the sun.

Learning to recognize the experience helps strengthen it, and at times, we might even evoke it deliberately. The upper-body posture of Buddha images, with the chest slightly forward, conveys confidence. Sitting in this way helps us touch into our own saddhā, even if it feels weak.

Actions

Faith is meant to have a motivational aspect also. As the first of the Five Spiritual Faculties, faith includes the willingness to put effort (the second faculty) toward something we value. When we have faith, we will put out energy; conversely, we are unlikely to make effort toward things in which we have no faith.

Thus, many actions arise from, or are expressions of faith. But it is also true that these same actions can evoke faith. Perhaps the quintessential act of Buddhist devotion is taking refuge in Buddha, Dhamma, and Sangha. This is done formally on retreats and sometimes in ceremonies offered at Dharma centers, but it can also be done simply before each sit or at times when the mind feels shaky.

When I participated in a simple but formal refuge ceremony at my first Dharma center, I was surprised that it brought forth powerful waves of joy (pītī) in my body. Something deep inside knew that this was important and right for me. Not being very interested in ceremony at the time, I discovered this new dimension of myself through the action.

Longer-term actions that support confidence include going on retreat or doing certain kinds of compassionate service. In reaching out beyond our own needs and typical daily patterns, we can strengthen the heart’s capacity to meet challenges in wholesome, wise, and flexible ways.

There are also many other devotional actions. Reciting or chanting the Dharma, ritual, bowing, and prayer are all options that are available, even within the early Buddhist and Theravāda traditions, which generally have fewer such things than other forms of Buddhism. Done well, these acts reduce self-focus because they are not really about you. They are done as offerings, from whatever state of mind one is in at the time. We do the chant the same way whether we happen to be angry, tired, or joyful that day. Faith increases as we are less entangled in self and can simply connect with the heart qualities evoked by the devotion.

I have enjoyed working with my altar over the years. It always houses a few meaningful items, but they rotate in and out depending on what feels important in my practice. When I go to a self-retreat center, I spend some time the first day gathering items from nature to create a simple altar. I sit with it every day, and then have a ritual of re-scattering the items back to nature when the retreat is over.

Internal Refuge

As you can see, there are many ways to support saddhā. Not all of these are appropriate for everyone, or for all times. But if you have several in your toolbox, you can see what works in a given situation of waning saddhā.

Perhaps the hardest part is remembering to check this list, which is why it is best to experientially explore it, so it gets into your bones, so to speak. In that way, these actions and mindstates become available to serve the path when needed. They become refuges.

Eventually, the heart can supply its own refuge, either by spontaneously doing one of the above, or through accessing its own deep confidence, wisdom, love, or compassion. Simply touching into our own heart can summon saddhā once we have practiced thoroughly with some of the items above.

Perhaps it is interesting to try a new one?